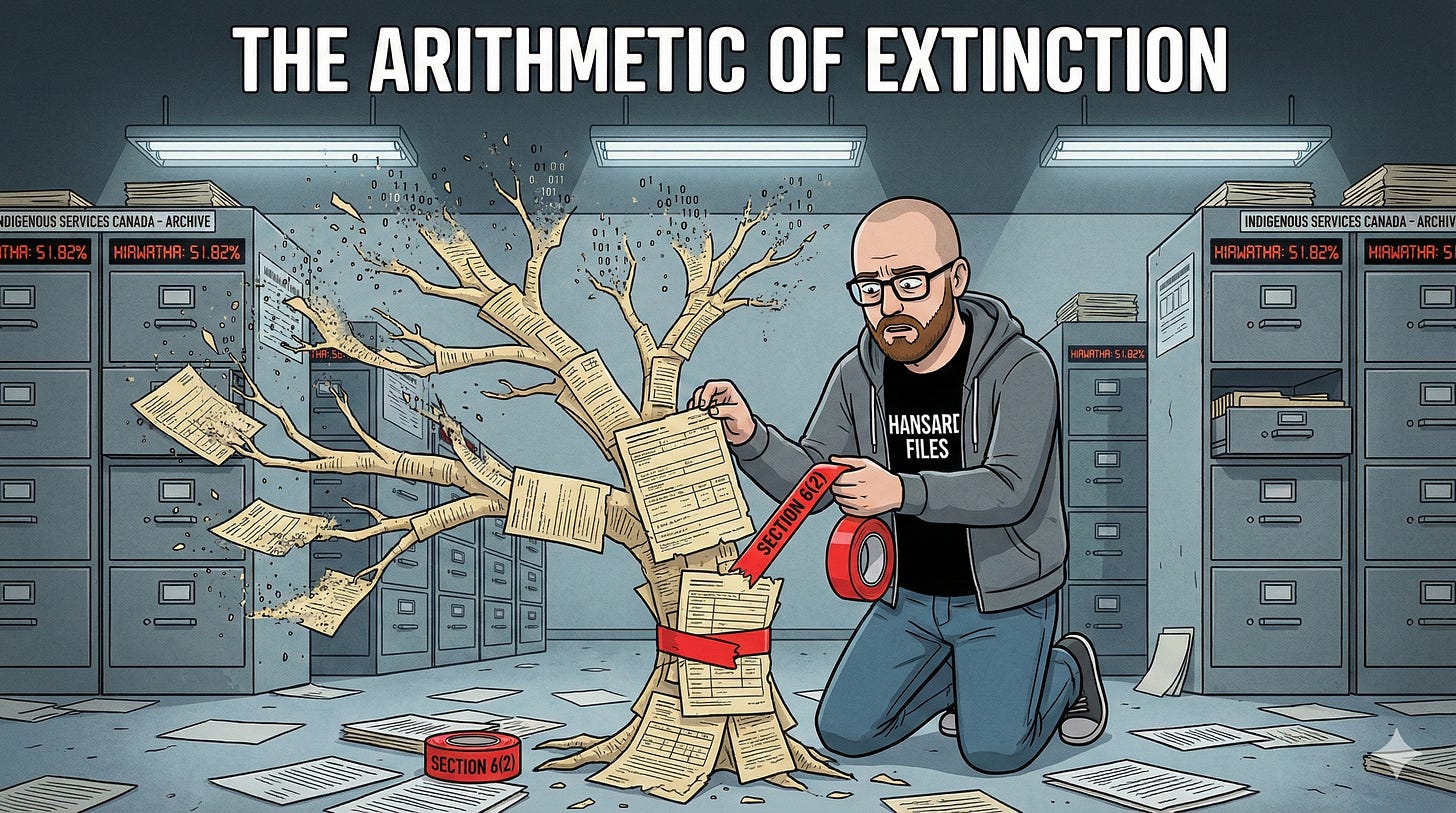

51.82% of Hiawatha: The Arithmetic of Extinction

Across Canada, a silent demographic clock is ticking inside the government’s own servers. New data reveals precisely when First Nations communities will legally cease to exist.

Deep in the administrative archives of Indigenous Services Canada, there is a spreadsheet entry for the Hiawatha First Nation that reads like a demographic autopsy. It notes that as of December 31, 2024, exactly 51.82% of the community’s registered population is categorized under Section 6(2) of the Indian Act.

To the bureaucrat, this is a data point. To the Hiawatha First Nation, it is a flashing red light. It means that the majority of their registered citizens have now crossed a legal threshold where they possess “Indian status” but cannot pass it on to their children unless they parent with another status holder. The moment a Section 6(2) individual has a child with a non-status person, the legal line ends. That child is born without status, cut off from their rights, their land base, and their federal recognition.

The Hiawatha number is not an outlier; it is a forecast.

Throughout 2024 and early 2025, the federal government generated “Community-Specific Data Sheets” for First Nations across the country, ostensibly to support a “collaborative process” on registration reform. But the resulting documents, when read together, reveal a national crisis of “legislated extinction.” From the Atlantic coast to the Yukon territory, the government is tracking the precise rate at which First Nations are being statistically erased by the very laws designed to manage them.

The Section 6(2) Trap

The mechanism of this erasure is not biological; it is purely statutory. Under the convoluted math of the Indian Act, status is not a birthright of ancestry alone—it is a legal categorization that degrades over generations of “out-marriage.”

A person with full Section 6(1) status can pass that status to their children regardless of who the other parent is. However, their child—if the other parent is non-status—receives only Section 6(2) status. This is the half-life of Indigenous identity under Canadian law. A Section 6(2) parent is legally sterile in terms of transmitting status if they partner with anyone other than another status Indian.

The government’s own files describe the “Second-Generation Cut-off” with chilling clarity: “The second-generation cut-off occurs after two consecutive generations of parenting with a person who is not entitled to registration, resulting in the third generation being no longer entitled”.

When a community’s population shifts so that 30%, 40%, or 50% of its members are in the 6(2) category, the pool of eligible partners shrinks mathematically. The “cut-off” becomes a self-fulfilling cycle. The Hiawatha First Nation has already tipped past the halfway point. They are living in the demographic future that awaits the rest of the country.

The Atlantic Crisis: “The Cliff is Here”

The data sheets reveal that the “cut-off” is not hitting every region equally. In the Atlantic provinces, the numbers suggest an immediate existential threat.

The Woodstock First Nation in New Brunswick has a registered population of 1,222 people. According to the federal ledger, 576 of those individuals—47.14%—are currently listed under Section 6(2). This effectively means that nearly half the community is one relationship away from ending their legal lineage. In a community of that size, finding a partner with status to “save” the legal identity of your children becomes statistically difficult, accelerating the erasure.

The numbers are equally dire in Quebec. The Wolf Lake First Nation, a smaller community with a total registered population of 290, has 122 members listed as Section 6(2). That is 42.07% of their people. When nearly half of a small population cannot transmit rights to the next generation, the legal dissolution of the band isn’t a matter of centuries—it is a matter of decades.

The Ontario Divide

Ontario presents a fractured landscape, illustrating how the Indian Act strikes differently depending on local demographics and history. While Hiawatha sits at the extreme end with 51.82%, other communities are following the same trajectory at different speeds.

The Zhiibaahaasing First Nation has 28.43% of its 197 members listed as Section 6(2). Meanwhile, the Iskatewizaagegan #39 Independent First Nation shows 27.50% of its 720 members in the cut-off category.

While 27% may seem “safe” compared to Hiawatha’s 51%, the government’s documents frame it as a critical loss of continuity. The files explicitly state: “This means that, as of December 31st 2024, 27.50% of Iskatewizaagegan #39 Independent First Nation’s population are not able to pass on entitlement to their children”. The government is not warning them of a future possibility; it is informing them of a current reality.

The Western Slow Burn

As we move west, the numbers shift but the pattern remains relentless. In the Prairie provinces, where Indigenous populations are larger and more concentrated, the percentages are slightly lower but pertain to much larger raw numbers of people—meaning thousands are affected.

In Manitoba, the York Factory First Nation has 25.04% of its 1,669 members listed under Section 6(2). In Saskatchewan, the Zagime Anishinabek faces a steeper cliff: 39.35% of its 1,860 members are cut off from transmitting status. That is over 730 people in a single community who are the last line of legal defence for their descendants’ identity.

Alberta’s Woodland Cree First Nation registers at 30.23%. Again, the consistency is haunting. Regardless of treaty status, location, or history, the Indian Act’s math grinds every community toward the same zero-point.

The Northern Frontier

Even in the remote North, where isolation might be expected to preserve community homogeneity, the legal erosion is advanced.

The White River First Nation in the Yukon has a small population of 165, but 35.15% are already Section 6(2). In the Northwest Territories, the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, a major cultural hub, sees 33.95% of its 1,720 members falling into the cut-off trap.

The government compares these community numbers to the national average, which sits at 29.32%. This national average acts as a grim baseline: across Canada, essentially one in three registered First Nations people is currently unable to pass on their rights freely.

The Pacific Complexities

British Columbia offers a complex mosaic of data, perhaps reflecting its diverse history of unceded territories and modern treaties. The numbers here swing wildly, showing how the cut-off can ravage one community while sparing its neighbor—for now.

The Hesquiaht First Nation is approaching the national average at 27.76%. In contrast, the Yunesit’in Government is currently sitting at 16.21%. While this appears better, it is a temporary reprieve. As members move to cities for work or education and marry non-status partners, that percentage will climb. The Indian Act does not allow for reversal; it is a one-way ratchet.

The Bureaucracy of Disappearance

What makes these documents truly dystopian is their tone. They are not written as warnings of cultural genocide, but as administrative updates. They use the passive voice to describe the end of bloodlines.

“The second-generation cut-off occurs...”

“Individuals... differ in their ability to pass on entitlement...”

“Services Canada is seeking First Nations’ involvement...”

The government invites communities to “Get Involved” by scanning a QR code. It suggests a bureaucratic solution to a problem created by bureaucracy itself. But for the 576 members of Woodstock First Nation or the 399 members of Woodland Cree who are already Section 6(2), a consultation process is cold comfort. Their status is already compromised. Their children’s future is already subject to a federal coin toss.

The Hiawatha First Nation, at 51.82%, stands as the ghost of Christmas Future for every other band on this list. Once the majority of a population loses the ability to transmit status, the legal entity of the “First Nation” enters a death spiral. The land may remain, the memories may remain, but the “Indian” as defined by the Government of Canada will simply cease to be.

And according to the 2024 data sheets, everything is proceeding exactly according to plan.

The Hansard Files digs through the data dumps that define our lives. Subscribe now to help us uncover the stories hidden in the spreadsheets.

Source Documents

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community-Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Yukon [Catalogue: R119-20/1-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community-Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Saskatchewan [Catalogue: R119-20/2-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community-Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Quebec [Catalogue: R119-20/3-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Ontario [Catalogue: R119-20/4-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community-Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Northwest Territories [Catalogue: R119-20/5-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community-Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): British Columbia [Catalogue: R119-20/6-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community-Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Atlantic [Catalogue: R119-20/8-PDF].

Indigenous Services Canada. (2025). Community Specific Data Sheets on the Impact of the Second-Generation Cut-off (As of December 31, 2024): Alberta [Catalogue: R119-20/9-PDF].

To be honest, Hansard, I don’t know what to think of this article. I would never think of impugning Indigenous peoples and their treaty rights but it seems logical that over time the percentage of indigenous roots are diminished? Sorry that doesn’t sound right..

On another note, I should research “The Indian Act” and observe what contemporary legislative changes have been made. I have always hated this title when referenced in media stories or other articles. To me it smacks of the very problematic colonial mindset we are trying to remove from our laws and society.

I wonder if this is why so many of the FNs get all bent, twisted & ugly about "Pretindians" as they call them. Accusations of people attempting to leverage a minimal amount of indigenous heritage to gain advantages off or on reserve happen frequently.

Their zealous protection of bloodlines makes sense if that's the primary link to the lucrative protections of Indian Act, although it seems to me the Indian Act is the primary underpinning of the Aboriginal Grievance Industry rather than serving native populations.

For disclosure, my own heritage includes a dribble of native blood. Although we never lived on a reserve, my father (RIP) qualified for an FSC fishery license; my sisters qualified for such as well. I expect I would qualify but I'm not interested. I fundamentally disagree with racial segregation. Whether it's "affirmative action" or "reserves", all forms of DEI are neoMarxist toxins designed to destroy western societies.