The Secret Memo That Forced Canada To Choose Sides

A classified request from Belgium tested national loyalty and trapped peacekeepers in the deadly crossfire of the Cold War.

The document landed on the desk of the Secretary of State for External Affairs with the dull thud of a diplomatic hand grenade. It was stamped “TOP SECRET” and “CANADIAN EYES ONLY.” The date was January 12, 1961. The file number was DEA/6386-40. Inside, the cool, bureaucratic language of the Under-Secretary of State masked a request that threatened to tear the Western Alliance apart and plunge the Congo Crisis into a full-scale proxy war.

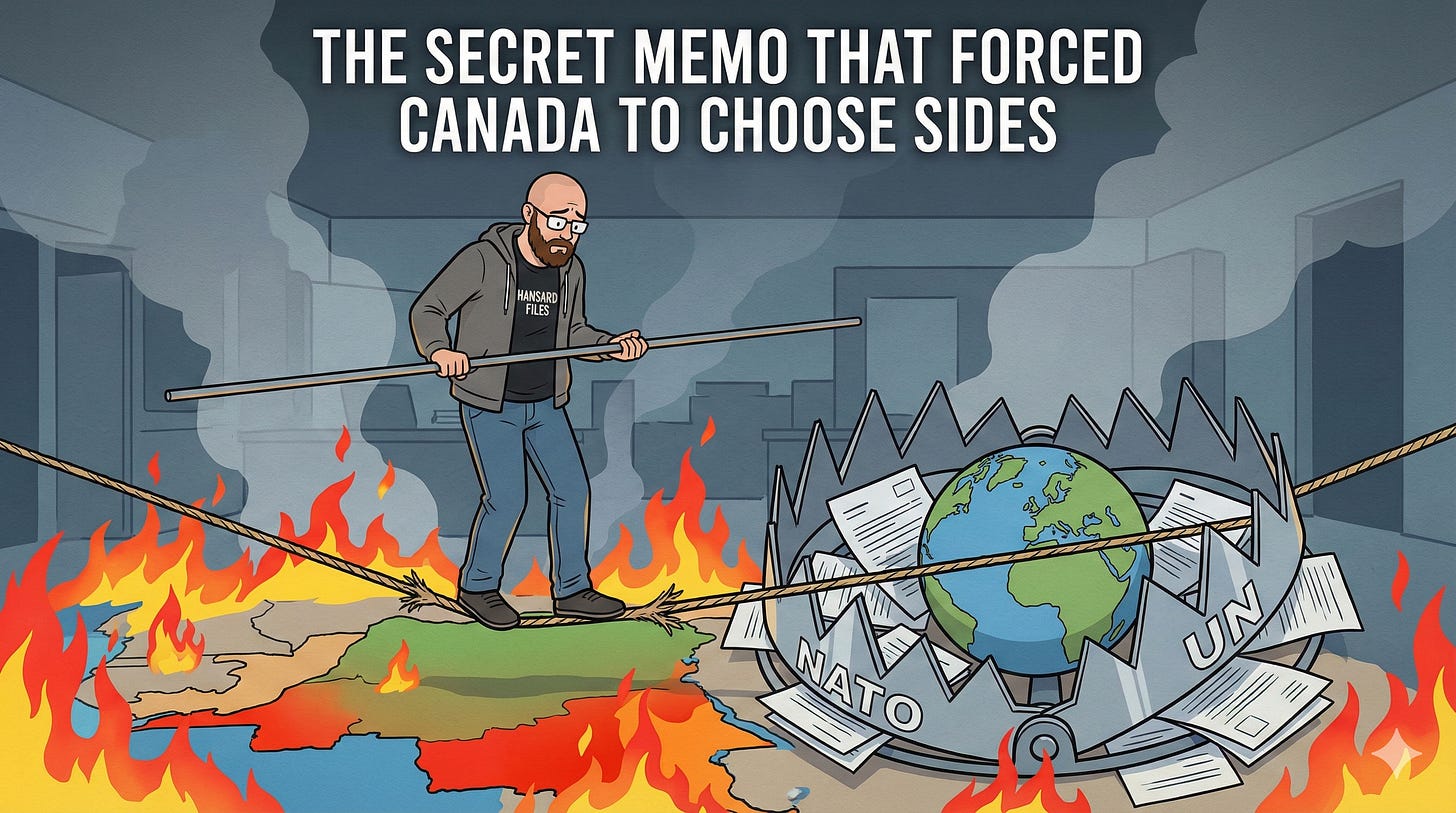

Belgium, a NATO ally, was asking for help. Their Ambassador, Baron Rothschild, had stood before the Political Advisors’ Committee of NATO two days earlier and requested “Western solidarity.” The request seemed simple on the surface: support Belgium’s decision to allow Colonel Mobutu’s troops to cross through the Trust Territory of Ruanda-Urundi to attack pro-Lumumba forces in the Congo. But in the quiet corridors of Ottawa, the implications were terrifying. Acceding to the request meant siding with a colonial power against the United Nations. Refusing it meant abandoning a key NATO ally in its hour of desperation. Canada was walking a tightrope over a burning country, and the cable traffic from 1961 reveals just how close the peacekeepers came to falling into the fire.

The Belgian Trap

The crisis had been brewing since the Congo won independence in June 1960, but the January 12 memo marked a dangerous escalation. The Belgians claimed they had been presented with a fait accompli. According to their account, Colonel Mobutu’s troops—about 200 of them—had landed at Usumbura in five commandeered aircraft. The Belgian authorities, claiming they had no time to consult Brussels, allowed the troops to land and even transported them to the Congolese frontier by truck.

This was not a humanitarian mission. These troops were on their way to Bukavu to fight forces loyal to Patrice Lumumba, the deposed Prime Minister whose shadow loomed large over the fractured nation. The Belgians argued that “Belgium and the West have both an interest and a moral responsibility in the Congo.” They warned that the United Arab Republic and Communist powers were bent on setting up a separatist government in Orientale Province. Their pitch was blunt: the West needed to present a united front against “Communist-Afro-Asian unity.”

For Canadian diplomats, the Belgian story had holes. The memo noted with icy skepticism that “it was no secret that some sort of expedition was planned” and that the requisition of aircraft was public knowledge. It seemed impossible that Belgium was unaware of the operation. The assessment from External Affairs was scathing: the Belgian authorities had likely acted contrary to the UN General Assembly resolution forbidding military assistance. The recommendation to the Minister was stark. Canada should not respond to Belgium’s appeal for NATO solidarity. The logic was cold and pragmatic: “NATO solidarity as such is not essential in a UN context.”

The Shadow of Lumumba

While diplomats in Ottawa and Brussels debated the finer points of international law, the situation on the ground was disintegrating. By mid-January, the specter of Patrice Lumumba—imprisoned since December—haunted every decision. On January 25, a confidential memorandum discussed the “Recommendation of Congo Advisory Committee for Release of Mr. Lumumba.” The UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld, had taken the bold step of recommending Lumumba’s release to participate in political negotiations.

It was a desperate gamble to stave off civil war. The Canadian diplomats noted that opposing the release of political prisoners would be difficult, yet they worried about the timing. They argued Lumumba should be treated by “due process of law.” But the cables reveal a grim irony that the diplomats in Ottawa could not yet know. A footnote in the archives confirms the brutal reality: Lumumba had already been killed on January 17, 1961. The diplomatic machinery was debating the fate of a ghost.

When the news of Lumumba’s death was officially confirmed in mid-February, the reaction was explosive. The Soviet Union, seeing an opportunity to cripple the UN operation, demanded the dismissal of Hammarskjöld and the withdrawal of UN forces within a month. They recognized Antoine Gizenga, Lumumba’s deputy, as the head of the legitimate government. The Congo was no longer just a chaotic post-colonial state; it was the new frontline of the Cold War.

The Man in the Middle

Caught in this geopolitical vice was Dag Hammarskjöld. The Canadian documents paint a portrait of a Secretary-General operating as a “lone wolf,” isolated and under siege. A confidential memorandum from the United Nations Division in April 1961 offered a candid assessment of the man at the center of the storm. It noted that Hammarskjöld had consistently worked to “maintain dignity and justice,” but his administrative style left him vulnerable. He relied on a tight inner circle, bypassing the Soviet-headed Department of Political and Security Council Affairs. This gave the Soviets ammunition for their attacks, allowing them to claim bias.

The Canadian assessment was blunt: “In my view, he has very little administrative sense.” Yet, the same memo acknowledged that the member states had developed a habit of “letting Dag do it.” When the Security Council or General Assembly was paralyzed by indecision, they passed vague resolutions and left Hammarskjöld to interpret them. In the Congo, this policy of ambiguity had fatal consequences. The Secretary-General was forced to make political decisions that inevitably alienated one side or the other. When he moved against the mercenaries in Katanga, the West cried foul. When he refused to use force against the secessionists, the Afro-Asian bloc accused him of colonial bias.

This reliance on one man became a critical weakness. As the crisis deepened, the strain on the UN machinery—and its finances—became unbearable. The “Fifth Committee” report from April 1961 reveals a profound weariness among the delegations. Representatives spoke resignedly of the end of the Organization. The Latin American bloc was “deeply emotional” about the costs, refusing to pay for a mess they felt was created by the Great Powers. The French were obstructing. The Soviets were refusing to pay a dime. Canada, along with a handful of other nations, was left scrambling to find a formula to keep the peacekeepers funded and fed.

The Katanga Tinderbox

By late 1961, the focus had shifted to the secessionist province of Katanga. Moise Tshombe, backed by powerful mining interests and European mercenaries, was defying the Central Government and the UN. The situation exploded in September and again in December.

The Canadian government found itself facing a new and more dangerous request. The UN needed air support. They needed fighter jets to counter the “Fuga” aircraft used by Katanga forces against UN troops. A secret memorandum from September 22, 1961, detailed the request: transport aircraft, aircrews, and technical assistance.

The Cabinet debate on September 23 was tense. The Secretary of State for External Affairs, Howard Green, laid out the dilemma. Providing aircraft would expose them to attack. But refusing would impair the UN’s influence. The Minister of National Defence, Douglas Harkness, reported that the UN needed C119 aircraft and technicians. The Cabinet agreed to send two aircraft for one month. It was a cautious toe-dip into a combat zone.

But the UN’s appetite for support grew as the fighting intensified. In October, they asked for control tower officers to assist the Swedish and Ethiopian jet fighters. The request forced Ottawa to confront the reality of the mission. This was no longer peacekeeping; it was peace enforcement. A memorandum from October 17 warned that “we could be placed later on in an awkward position if the U.N. engages in warlike operations.”

The internal friction within the Canadian government is palpable in the documents. By December 7, Minister of National Defence Harkness had had enough. In a confidential letter to his colleague Howard Green, he argued strongly that the position of Air Commander in the UN Force should no longer be filled by a Canadian. He pointed out that the role of the force had changed from maintaining law and order to “defensive and offensive military operations.” The UN jets were attacking Katanga airfields. Harkness wanted out.

Green pushed back. In a memo dated December 15, he argued that withdrawing the Canadian Air Commander at the height of the fighting would be interpreted as “disapproval of the U.N.’s current operations.” It would signal a crack in Western support just when unity was most needed. The compromise was typical of Canadian diplomacy: postpone the repatriation for three months, wait for the dust to settle, and avoid taking a public stand that would embarrass the UN.

The Fog of War

The confusion on the ground in late 1961 was absolute. A telegram from the Canadian Consul General in Leopoldville in September 1961 offered a scathing critique of the UN’s “Operation Morthor,” the attempt to round up mercenaries in Katanga. “I find little justification for recent UN action,” he wrote. He argued that the UN had underestimated the will of the Katanga army to resist and had acted on a “hastily conceived” plan. He warned that by using force to settle an internal political issue, the UN had set a “dangerous precedent.”

This view from the field clashed violently with the perspective from New York. There, Canadian diplomats were frantically trying to shield the UN from criticism while urging the Secretariat to explain its objectives. A telegram from September 15 noted that the Irish Permanent Representative was “very much concerned about the lack of adequate information.” Irish troops were cut off and under fire in Jadotville, and the UN in New York seemed to be operating in a fog.

Then came the tragedy that defined the era. On September 18, 1961, Dag Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash while flying to negotiate a ceasefire with Tshombe. The Canadian documents refer to it simply as the “untimely death of Mr. Hammarskjöld,” but the diplomatic fallout was immediate. The UN was left in a “legal vacuum.” The extremists in both Leopoldville and Katanga were emboldened. The center could not hold.

The Mercenary Problem

The final act of 1961 revolved around the “mercenaries”—the European soldiers of fortune propping up Tshombe’s regime. A Security Council resolution in November authorized the use of force to apprehend them. This terrified the British, who feared it would lead to a “scorched earth” policy by the Union Minière, the mining giant that controlled Katanga’s economy.

A secret memo from December 15, 1961, outlined the nightmare scenario: the mercenaries, acting as agents of the Union Minière, might destroy the mines, power stations, and dams rather than let them fall to the Central Government. The Canadian assessment was pragmatic. Evicting the mercenaries by force was “virtually impossible” as they could melt into the civilian population. The only solution was to cut off their paymasters. The memo suggested a back-channel deal: persuade the Union Minière that their only hope of business survival lay in cooperation with the UN and the Central Government.

As the year ended, UN troops were engaged in a ground offensive in Elisabethville. The “peacekeeping” mission had become a war of reconquest. The Canadian government, which had hesitated to send technicians a few months earlier, watched as Indian Canberras bombed Katanga airfields and Swedish troops fought street-to-street battles. The “neutral” Congo that Canada had hoped to preserve was gone, replaced by a battlefield where every decision was a choice between bad options.

The archives of 1961 do not end with a victory parade. They end with a cease-fire that was barely worth the paper it was written on, a dead Secretary-General, and a Canadian government that had learned a hard lesson: in the heart of darkness, even the white flag of the United Nations offers no protection against the crossfire of history.

Source Documents

African and Middle Eastern Division. (1961, January 12). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-40).

African and Middle Eastern Division. (1961, November 17). Memorandum from Head, African and Middle Eastern Division, to Special Assistant to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-40).

African and Middle Eastern Division. (1961, December 20). Visit of Congolese Delegation to Canada (DEA/6386-D-40).

Barton, W.H. (1961, January 16). Memorandum from Head, Defence Liaison (1) Division, to Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-40).

Cabinet Conclusions. (1961, February 16). Extract from Cabinet Conclusions (PCO).

Cabinet Conclusions. (1961, September 23). Extract from Cabinet Conclusions (PCO).

Cabinet Conclusions. (1961, October 23). Extract from Cabinet Conclusions (PCO).

Cabinet Conclusions. (1961, November 3). Extract from Cabinet Conclusions (PCO).

Gauvin, M. (1961, September 16). Telegram 253 (DEA/6386-40).

Green, H.C. (1961, January 20). Telegram ME-13 (DEA/6386-L-40).

Green, H.C. (1961, September 20). Telegram ME-464 (DEA/6386-40).

Harkness, D.S. (1961, December 7). Letter to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-C-40).

Murray, G.S. (1961, April 11). Memorandum from United Nations Division to Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/5475-6-40).

Murray, G.S. (1961, December 15). Memorandum from United Nations Division to African and Middle Eastern Division (DEA/6386-40).

N’Krumah, K. (1961, May 5). Telegram E-825 (J.G.D./01/XII/F/215).

Ritchie, C.S.A. (1961, February 3). Telegram 220 (DEA/6386-40).

Ritchie, C.S.A. (1961, February 14). Telegram 268 (DEA/6386-40).

Ritchie, C.S.A. (1961, September 15). Telegram 1895 (DEA/6386-40).

Ritchie, C.S.A. (1961, November 1). Telegram 2473 (DEA/6386-40).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, January 12). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-40).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, January 25). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-40).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, May 10). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Prime Minister (J.G.D./01/XII/F/215).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, September 20). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Prime Minister (DEA/6386-40).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, September 22). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-C-40).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, October 17). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-C-40).

Robertson, N.A. (1961, December 15). Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs (DEA/6386-C-40).

United Nations General Assembly. (1961, April). Extract from Final Report of the Fifteenth Session, Fifth Committee (DEA/6386-H-40).

Fascinating!

Damn!! First I ever heard of this debacle!! Thanks for that!!